The hidden secrets buried in some of the world's most famous artworks

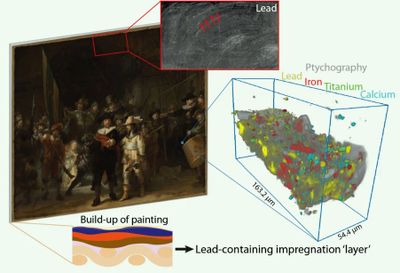

New research has solved a decades-old mystery about a hidden layer beneath one of Rembrandt's masterpiece The Night Watch.

Art experts used X-rays to examine the painting depicting 18th-century Dutch military volunteers gathering for duty.

Below the varnish and paint, they discovered a previously unrecorded layer of lead, a feature that had never been seen before in Rembrandt's works.

The lead-saturated layer may have been used instead because it could better protect the canvas, the study published in the journal Scientific Advances suggested.

When the painting was completed in 1642, it was hung in a musketeers' shooting range, on a wall facing a row of windows, where it would have been vulnerable to damage from moisture.

The discovery of the lead layer also helps explain the decades-old appearance of tiny "pimples" of lead crystals on the painting that rose to the surface seemingly out of nowhere.

Italian Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci may have been in a particularly experimental mood when he set to work on the "Mona Lisa", early in the 16th century, new research shows, reports AP.

Using X-rays to peer into the chemical structure of a tiny speck of paint from the world's most famous painting, researchers found a rare compound, plumbonacrite, in Leonardo's first layer of paint.

It confirms long speculation that Leonardo most likely used lead oxide powder to thicken and help dry his paint as he began working on the portrait that now stares out from behind protective glass in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

The scientists peered into its atomic structure using X-rays in a synchrotron, a large machine that accelerates particles to almost the speed of light.

It's hard to quantify the value of painter and all-around cultural icon Bob Ross, but US$9.85 million ($15.31 million) is a good start.

The very first on-air painting from the very first episode of Ross' beloved series "The Joy of Painting" is looking for a new owner after being kept safe for decades by one of the show's early volunteers.

"A Walk in the Woods" was painted live on-air in January of 1983, and typifies everything the public came to love about Ross and his art-positive mission. It depicts a placid woodland scene in shades of gold and blue, painted with Ross' preferred "wet on wet" technique, with deceptively complex-looking brushstrokes and, of course, an abundance of happy little trees.

It has been verified as authentic by Bob Ross Inc.

A close-up of the work shows Ross' iconic signature.

Modern Artifact owner Ryan Nelson said Ross' work has seen increasing demand over the years.

"The driving force behind the increased demand for Bob Ross paintings seems to be collectors themselves," Nelson said in a statement.

"Nostalgia, social media and an increased interest by the general public in the personality behind the art have all contributed to his current popularity."

The gallery is offering the painting at a price point of US$9.85 million, but Nelson says it's in no rush to sell.

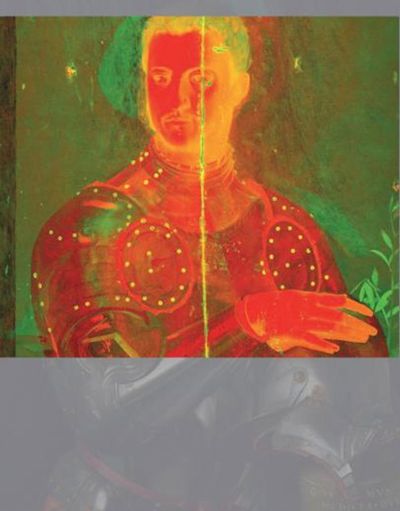

For 40 years, curators at the Art Gallery of New South Wales have known there was something hiding underneath this Renaissance painting.

But it took the collaboration of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation to finally solve the mystery.

X-rays taken in the early 1980s showed there was an underpainting beneath Cosimo I de' Medici in armour by Agnolo di Cosimo.

But an advanced imaging technique at the Australian Synchrotron has finally revealed it.

The technique can reveal specific metals which were commonly used in Renaissance paints, including mercury, copper, tin, iron and manganese.

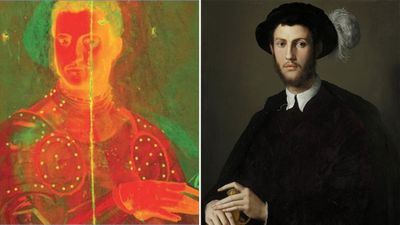

Curators believe the underpainting may have been a draft for another painting, Portrait of a young man.

Side by side, the shapes of the underpainting resemble the outline of the latter painting.

Click through to see more hidden paintings within paintings.

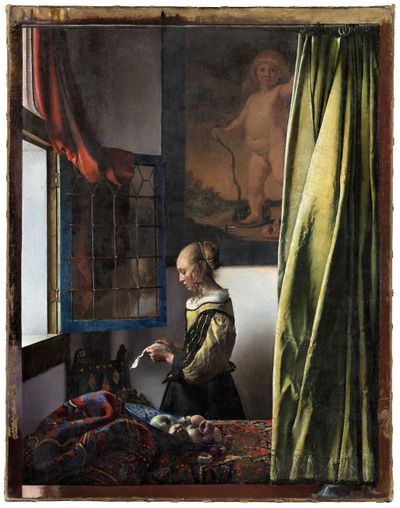

For centuries, Johannes Vermeer's Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window has been regarded as a masterpiece of the Golden Age of Dutch art.

But it has only been in recent years that experts have noticed the painting within a painting.

At some point in between 1659 and now, a painting on the wall in the portrait had been covered over.

Now, after two-and-a-half years of meticulous scraping with a scalpel, the true image has finally been unveiled.

The artwork as Vermeer painted it shows a picture of a naked Cupid on the wall, behind the girl reading a letter.

It is now on display at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany.

This 1434 oil painting by Dutchman Jan van Eyck may seem like a pretty conventional portrait of a merchant, his pregnant wife and their dog.

But look closer. Not only has van Eyck written his name at the centre of the piece, he's painted himself into it.

"Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434," the words at the centre of the painting read, translated to Jan van Eyck was here, 1434".

But underneath the message is a small circular mirror. In it, you can see the backs of the subjects, and in the middle, the painter himself.

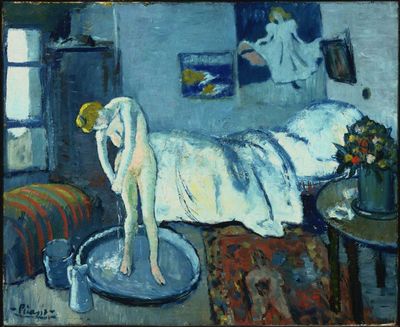

Pablo Picasso's 1901 piece The Blue Room was considered one of the most important pieces for the young artist.

But after decades on display in Washington DC, x-ray and infrared scans revealed there was a hidden painting underneath.

The original painting shows a bow-tied man glaring at the painter.

As a 19-year-old struggling painter, Picasso was often unable to sell his paintings, so to save the canvas, he would often paint over old portraits.

There's also hidden faces in Picasso's famed work The Old Guitarist.

Look at the centre of this image, and you'll see a woman's face under the top layer of paint.

The face has a ghostly presence in the artwork, but is likely just the result of a recycled canvas.

Hans Holbein the Younger's painting The Ambassadors seems like a conventional Tudor period portrait.

In the painting are French diplomats Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, a globe, a carpet, and on the ground, an anamorphic skull.

Viewed from the front on, the skull may not stand out. But it is hypothesised the painting was meant to hang in a stairwell, so a person walking up the stairs would be startled by the macabre Easter egg.

For centuries, Dutch painter Hendrick van Anthonissen's View of Scheveningen Sands was simply a painting on the beach.

But in recent years, experts started to speculate: what are all these people on the beach looking at.

Then in 2014, the painting came to Hamilton Kerr Institute for cleaning. There they started to strip off the thick layers of varnish and overpainting, and discovered a shocking edit.