An excavation in Norway has uncovered dozens of ancient children's graves beneath arranged stone circles.

More than 40 graves were discovered during the work, which began in 2023.

All but two of them belonged to children, most aged between three and six, the Museum of Cultural History said in a statement.

The graves date back to between 800 BCE and 200 BCE, suggesting the site was in use for centuries.

Some of the stones displayed carvings of voyages and sun worship.

"The field of children's graves is unique in a Norwegian context, and opens up many questions to which the answers are still unknown," the museum said.

"Why were the children buried in a separate place? Why here? And how did they hold on to this tradition for several hundred years?"

New images have emerged of a temple precinct dating back up to 5000 years in Peru.

The stunning discovery had been buried under a sand dune in the Zaña District (also known as the Saña District).

"We are probably looking at a 5000-year-old religious complex that is an architectural space defined by walls built of mud," Dr Luis Armando Muro Ynoñán, director of the Archaeological Project of Cultural Landscapes of Úcupe - Zaña Valley, said in a translated statement from the Peruvian government.

"We have what would have been a central staircase from which one would ascend to a kind of stage in the central part."

Still-highly defined friezes in the temple depitcted "a human body with a bird's head, feline images and reptile claws", researchers said in the statement.

"Special ceremonies were held here and a wall covered with fine plaster with a pictorial design was discovered on the upper part," the statement read.

Another dig in the same area is believed to date back to a relatively recent era, in 600-700 CE, when the Moche culture held sway in the region.

The body of a small child, aged five to six years old, was found interred there.

While the Moche are believed to have practised human sacrifice, the child's burial dates to a still-later period, researchers said.

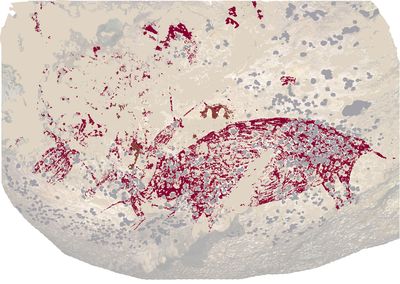

In a groundbreaking development for our understanding of the origins of early art, the world's oldest known reliably-dated cave art image has been discovered.

Found inside this limestone cave named Leang Karampuang on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, it is the oldest known evidence of storytelling in art.

"Our results are very surprising," lead researcher and Indonesian rock art specialist Adhi Agus Oktaviana said.

"None of the famous European Ice Age art is anywhere near as old as this, with the exception of some controversial finds in Spain, and this is the first-time rock art dates in Indonesia have ever been pushed beyond the 50,000-year mark."

The remains of the painting depicts three human-like figures interacting with a wild pig.

A joint team of Australian and Indonesian scientists used a new dating technique called laser ablation U-series analysis to date tiny layers of calcium carbonate that has formed on top of the art.

They found the underlying artwork was painted at least 51,200 years ago - making it the oldest known reliably dated cave art image in the world.

The researchers say the new, more accurate technique has the potential to "revolutionise" rock art dating.

"We have previously used the uranium-series method to date very old rock art in two parts of Indonesia, Sulawesi and Borneo, but our new LA-U-series technique is more accurate, allowing us to date the earliest calcium carbonate layers formed on the art and get closer to the point in time the art was created," said Griffith University archaeologist Professor Maxime Aubert.

A second ancient shipwreck has been discovered by divers off the Greek island of Antikythera, on the edge of the Aegean Sea.

Among the artefacts in the remains of the wooden vessel was this bronze toe from a statue dating back to about 60BC. It was uncovered by divers during an underwater excavation last month.

The second ancient shipwreck was found only 200 metres from another one off the island, discovered by sponge divers in 1900.

That one contained the famous Antikythera mechanism - the oldest known example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses. It is regarded as one of the cultural treasures of the ancient world.

A 2000-year-old Roman funerary urn unearthed in southern Spain has been shown to contain the oldest wine ever found still in liquid form.

Discovered during home renovations at a property in Carmona in 2019, the contents of the urn were analysed by a team of scientists from the University of Cordoba in a study published this month.

Study lead author José Rafael Ruiz Arrebola, a professor of organic chemistry at the university, told CNN that the urn was found to contain cremated remains, burned ivory thought to come from a funeral pyre and around 4.5 litres of reddish liquid.

"When the archaeologists opened the urn we almost froze," he said.

"It was very surprising."

The team then carried out a chemical analysis of the liquid and found that it was wine.

This was a big surprise, because wine normally evaporates quickly and is chemically unstable, Ruiz Arrebola said.

"This means it is almost impossible to find what we have found," he said, explaining that the wine had been preserved by a hermetic seal that prevented it from evaporating, but it is not clear how the seal formed.

Further chemical analysis allowed the team to identify the liquid as a white wine, as it didn't contain syringic acid, a substance only present in red wines, Ruiz Arrebola said.

It also has a similar mineral salt composition to the fino wines produced today in the region, he added.

"It's something unique," said Ruiz Arrebola.

"We have been lucky to find it and analyse it – it's something you only see once in your life."

The researchers believe their discovery dethrones the current holder of the record for oldest wine in a liquid state, the Speyer wine bottle, found in Germany, which is thought to be around 1700 years old. However, the age of the Speyer bottle has not been confirmed by chemical analysis.

The vessel was one of six funerary urns containing remains found in the mausoleum.

The discovery of a gold ring and other valuable artifacts suggest it was built by a family of considerable wealth, Ruiz Arrebola said.

However, little else is known about their lives, because cremation would have destroyed any DNA, he explained, adding that this means it is impossible to say whether the six people were related.

Ruiz Arrebola now plans to try to work out which modern-day local wine it was most similar to, although there are hundreds to work through.

The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

The mummified body of a 44,000 year old wolf has been recovered in frozen Siberia.

The unprecedented find was pulled from the permafrost in the Russian Republic of Sakhia.

It's the first adult wolf dating back to that era ever found, researchers at the North-Eastern Federal University said.

During a necropsy, researchers took samples to examine for possible diseases and dietary indications.

"His stomach has been preserved in an isolated form, there are no contaminants, so the task is not trivial," Albert Protopopov from Yakutia's Academy of Sciences said.

"We see that in the finds of fossil animals, living bacteria can survive for thousands of years, which are a kind of witnesses of those ancient times," ancient virus researcher Artemy Goncharov said.

Researchers examine the wolf's preserved organs.

Researchers in Spain were surprised to find the bones of a woman interred among those of about two dozen militant monks in an ancient Spanish castle.

Furthermore, the woman appeared to be no servant but a "female warrior", Universitat Rovira i Virgili researcher Carme Rissech said.

The bones were found in the Zorita de los Canes castle on the Tagus River in the Spanish province of Guadalajara. Initially built by the Muslim emir of Cordova Mohammed I in 852, the fortress swapped hands several times before the militant Order of the Temple (better known as the Knights Templar) conquered it in 1124.

Fifty years later, King Alfonso of Castile ordered the castle transferred to the guardianship of another militant religious brotherhood, the Order of Calatrava.

It is likely their bones, dated to the 12th to 15th centuries, which formed the remains studied by Rissech and her fellow researchers.

"We observed many lesions on the upper part of the skull, the cheeks and the inner part of the pelvis, which is consistent with the hypothesis that we are dealing with warriors," Rissech said in a statement.

One of the skeletons that had suffered such treatment had belonged to a woman.

"She may have died in a manner very similar to that of male knights, and it is likely that she was wearing some kind of armour or chain mail," Rissech said.

However, the mystery woman was also found to have had a poorer diet than the meat- and fish-heavy intake of the other knights.