Nearly two dozen cases of measles have been reported in the United States since December 1, according to an alert from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

International travel, coupled with declining global vaccination rates, is probably behind this spate of cases, experts say.

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health has confirmed at least nine cases of measles over the past month after a person contracted the highly contagious virus outside the United States and exposed a parent and child at a children's hospital, according to health department spokesperson James Garrow.

That exposure then led to a Philadelphia daycare outbreak that includes at least five children.

Health officials in Virginia are also warning people who recently travelled out of two DC-area airports – Dulles International Airport on January 3 and Reagan Washington National Airport on January 4 – of potential exposure to the virus after someone returning to the US from abroad travelled through Northern Virginia.

Additionally, a single case of measles has been confirmed in "an unvaccinated resident of the metro Atlanta area," the Georgia Department of Public Health announced this month.

"The individual was exposed to measles while travelling out of the country," a news release said. "DPH is working to identify anyone who may have had contact with the individual while they were infectious."

It's not only the United States. In the UK, a measles outbreak continues to widen: As of January 18, there have been 216 confirmed cases and 103 probable cases reported since October. The UK Health Security Agency has declared a national incident to signal the growing public health risk.

The virus has also been detected in Australia, where alerts have been issued by NSW, Victorian and ACT health authorities in recent weeks.

"It's always concerning when we have a case of measles because of the probability that it's going to spread to other individuals," said Dr Thomas Murray, a professor of pediatrics at the Yale School of Medicine who focuses on infectious diseases and global health.

"About 90 per cent of susceptible people who are exposed will come down with signs and symptoms of the disease, so it's very contagious."

Why is measles spreading?

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000, after zero virus spread for more than a year, largely due to a "highly effective vaccination campaign", according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, clusters in the US are still possible because the virus is not eliminated worldwide. There are several countries with active outbreaks.

"Many of the diseases for which we have vaccines have virtually disappeared from the United States but certainly not in other places around the world," Murray said.

If an unvaccinated person goes to a country where a disease is still common, becomes infected and brings it back to the US, Murray notes, they can spread the virus to other unvaccinated people.

"There's a lot of travel back and forth," he said.

"If there are pockets of unvaccinated individuals that are congregating closely together and that disease gets introduced into that population, you can have large clusters of cases."

Falling vaccination rates

Vaccination rates in the US also remain low, particularly among children, according to American Academy of Pediatrics spokesperson Dr Christina Johns, a Maryland-based pediatric emergency physician at a PM Pediatric Care urgent care.

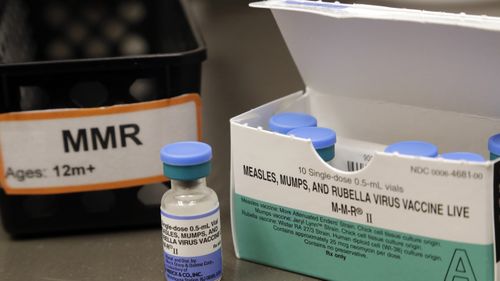

The CDC noted in its alert that the majority of the measles cases "were among children and adolescents who had not received a measles-containing vaccine (MMR or MMRV), even if age eligible."

About 92 per cent of US children have been vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella (called the MMR vaccine) by age 2, according to a 2023 report from the CDC – below the federal target of 95 per cent.

The percentage of kindergartners who got their state-required vaccines for measles also remained below the federal target for the 2022-23 school year, according to CDC data. And the rate of vaccine exemptions for children has reached the highest level ever reported in the US.

Children should get two doses of the MMR vaccine, according to the CDC: the first dose at 12 to 15 months of age and the second at four to six years of age.

Before the nation's measles vaccination program, about three to four million people got the virus every year, and about 400 to 500 died.

The last significant measles outbreak in the US was in 2018-19 in Rockland County, New York, focused among unvaccinated children in Orthodox Jewish communities.

Although the CDC reported only 56 measles cases in 2023, Johns says that is too many when a highly effective vaccine exists.

"Most people haven't seen a case of measles," she stressed. "They don't really have an appreciation for the severity of the illness."

Measles spread and symptoms

The measles virus can spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, lingering in the air for up to two hours after they leave a room, according to Murray. The virus can also live on surfaces such as doorknobs for about the same amount of time.

When symptoms begin, they're similar to those of many respiratory illnesses – high fever, cough, red eyes, runny nose and congestion – followed by a "fairly characteristic" rash, Murray said.

"You get flat red lesions, flat red spots that typically start on your face and move down across the body across the chest and trunk and extremities," he said. "It can be a total body rash, and it's pretty severe."

The incubation period for measles is very long, Murray adds. It takes about 10 to 12 days for initial symptoms to appear after exposure.

Because of this, most infected people assume their respiratory symptoms are nothing but a cold until the rash appears three to five days after the initial illness begins, according to Murray. Even then, most people – including some doctors – will not recognize a measles rash.

"Infected people are contagious from four days before the rash starts through four days afterwards," the CDC says.

"The younger the health care provider, the less likely they are to have seen a case," Murray said. "But certainly, when it's circulating, we do everything we can to get the word out on what to look for."

The CDC advises healthcare workers to isolate patients who may have measles in specific isolation rooms or private rooms instead of having them waiting in common areas; to test patients with suspected cases; and promptly alert state and local health departments.

Measles health risks

Lower MMR vaccination rates can put unvaccinated and undervaccinated individuals at risk, Johns says, especially children and those with immune system problems.

Measles can lead to serious complications, especially in children under two, such as blindness, encephalitis or inflammation of the brain, and severe pneumonia, according to Murray.

"Measles is also a virus that knocks down parts of the immune system," he said. "There's recent evidence that having measles increases your susceptibility to other infections."

A rare complication called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis can also happen seven to 10 years after infection and may result in seizures as well as behavioural and mental deterioration.

Additionally, someone who doesn't get the MMR vaccine is at risk of contracting mumps and rubella, which are rare but still in circulation in the US due to international travel.

In 2023, 436 mumps cases were reported by 42 jurisdictions, according to CDC data. Rubella is less common, with fewer than 10 people in the US getting the virus each year.

The latest COVID-19 strain spreading across the world

What to do if you were exposed to measles

If you're fully vaccinated against measles, your chance of infection after exposure is very low because the two childhood doses typically confer lifelong immunity, experts say.

"It's not impossible, but it's very, very low," Murray notes.

But for people who aren't unvaccinated or who have weak immune systems, the risk increases – "especially if they know they're in an area where measles has been circulating," he said. "In that case, what you would do is, you would call your health care provider and work with [them] to determine next steps."

If you think you might have been exposed to measles, stay home until a plan is in place, Murray advises.

"Call ahead before you go to any healthcare facility, because that healthcare facility can anticipate your arrival and make sure you are placed in the appropriate isolation rooms," Murray said.

"The last thing we want to do is have someone with measles sitting in the emergency room waiting room."

Unvaccinated people who know when they were exposed can get the MMR vaccine within 72 hours of exposure to prevent the disease altogether or lessen the severity of the illness, Murray adds.

As for treatment, the virus simply has to run its course, he says. There is no specific antiviral treatment, and medical care is mainly supportive: staying home from school or work to rest and drink plenty of fluids.

If a person infected with measles is showing symptoms of encephalitis, such as a headache, high fever or seizures, they should be taken to a hospital immediately.

"Typically, hospitalisation for measles occurs when children are in respiratory distress from lung involvement like pneumonia or are dehydrated and need IV fluids," Johns said.

Severe measles cases among children can also be treated with vitamin A, according to the CDC, to support the immune system.

"Vitamin A should be administered immediately on diagnosis and repeated the next day," the agency said.