February is running for one day longer than usual in 2024 thanks to it being a leap year.

While a relatively minor adjustment for everyone to make, the leap day actually serves a very important role in keeping our seasons in sync with the sun and moon, with a history going back thousands and thousands of years.

This is everything you need to know about leap years, February 29, and why they exist in the first place.

What is a leap year and why do they exist?

Leap years are, quite simply, a year that has 366 days instead of 365.

They exist because it takes roughly (but not exactly – more on that later) 365.25 days for Earth to orbit the sun, and so we need to add around one extra day to the calendar every four years.

What is the history of leap years? How did they even begin?

The history of leap years goes back thousands and thousands of years, all the way to the Bronze Age – that's about 3300-1200 BC – when many civilisations used calendars that added extra periods of time depending on the year.

The leap year really started to look like what we use today when Julius Caesar took charge of the Roman Empire. In addition to dealing with seasonal drift (we'll get into that shortly) he had to contend with a wide range of calendars being used across the realm.

His response was the Julian calendar, which came into effect in 46 BC. With the help of Ancient Egyptian astronomers from Alexandria, he calculated the year as 365.25 days long, so added an extra day every four years.

That day was always added to February, as the Romans had a long history of tinkering with the length of that particular month.

Thing is, the year isn't 365.25 days long. It actually lasts 365.242 days – a whole 11 minutes and 14 seconds shorter than what Caesar thought.

That miscalculation didn't have much of an impact in Caesar's time, and the Julian calendar was used across much of Europe for more than 1000 years. Indeed, it remains the basis for our modern-day calendar.

But by the 16th century AD, those 11 minutes and 14 seconds every year had added up to the point where Easter was falling later and later, and Pope Gregory XIII was worried about the prospect of it clashing with pagan festivals in the northern hemisphere spring.

So in 1582, he introduced the Gregorian calendar, which we still use today.

That involved cutting 10 days out of that calendar year to undo the inaccuracy of the Julian calendar, although not every country introduced the Gregorian calendar at the same time and those who adopted it later had to skip more days.

The United Kingdom and USA, for example, brought it into effect in 1752 and hacked out 11 days from September that year, while the likes of China, Russia and Turkey didn't adopt the modern calendar until the 20th century.

Post-colonisation Australia has always used the Gregorian calendar.

What years are leap years and when is the next one?

You've probably heard that leap years are held every four years.

But that's actually not quite the case. Under the Gregorian calendar, years divisible by 100 are not leap years unless they are also divisible by 400.

So 1700, 1800 and 1900 didn't have February 29, but 2000 did.

2024 is, of course, a leap year, and the next ones will be observed on 2028, 2032, 2036 and 2040.

The Gregorian calendar isn't perfect. While the pope's boffins pulled off some seriously impressive maths for the 16th century, they weren't 100 per cent accurate, missing the mark by a whole 27 seconds a year.

That means that we'll accrue a whole extra day every 3236 years, which will be a problem for people living around the 49th or 50th century AD.

What would happen if we didn't have leap years?

As mentioned earlier, the problem Caesar and Gregory were dealing with was "seasonal drift" – that is, seasons, major events and agricultural planting schedules falling out of alignment with the sun and moon.

"Without the leap years, after a few hundred years we will have (northern hemisphere) summer in November," Younas Khan, a physics instructor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said.

"Christmas will be in summer. There will be no snow. There will be no feeling of Christmas."

That sounds a lot like saying all of the northern hemisphere would eventually get to experience an Australian-style Christmas.

What leap year traditions and superstitions are there?

Bizarrely, February 29 comes with lore about women popping the marriage question to men, although no one really knows where or when the tradition began.

It was mostly benign fun, but it came with a bite that reinforced gender roles.

There's distant European folklore. One story places the idea of women proposing in fifth-century Ireland, with St Bridget appealing to St Patrick to offer women the chance to ask men to marry them, according to historian Katherine Parkin in a 2012 paper in the Journal of Family History.

Advertising perpetuated the leap-year marriage game. A 1916 ad by the American Industrial Bank and Trust Co. read thusly:

"This being Leap Year day, we suggest to every girl that she propose to her father to open a savings account in her name in our own bank."

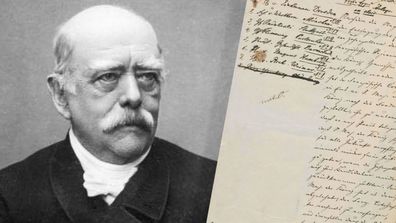

He wrote 105 words so offensive they sent two world powers to war

There was no breath of independence for women due to leap day.

While some cultures believe marrying on February 29 is bad luck, plenty of people still choose to tie the knot on leap day, which may or may not have anything to do with only remembering an anniversary once every four years.

As for birthdays, there are about 5 million people worldwide who share were born on February 29 out of about 8 billion people on the planet.

- With Associated Press